For at least 113 years, humans have stereotyped Martians as invaders, as butchers, as sadists, as strange-looking monsters, and even as rapists of white women.

To humans, Martians are truly the Other. They are otherworldly. Alien. Unknown and unseen, they provide a canvas on which humans write their worst fears. These stereotypes are defined by humanity, in the absence of actual Martians, as being everything humanity is not.

Not surprisingly, these stereotypes have often succeeded in climates rife with human racism, demonstrating the tight connection between planetism and inner-species racism. The parallels, right down to specific composition of images or fears of miscegenation, are close enough that they ought to dispel any rational doubts that anti-Martian sentiment stems from the same ugly side of humanity that fears the Other, whether extra-planetary or simply of a different race of humans.

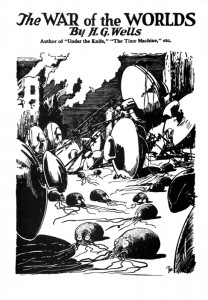

War of the Worlds

The most prominent strain in Martian stereotypes — that of Martians as cruel and hostile invaders — comes from War of the Worlds, the famous 1898 novel by H. G. Wells. Its success set the standard for all such stereotypical stories to come.

The most prominent strain in Martian stereotypes — that of Martians as cruel and hostile invaders — comes from War of the Worlds, the famous 1898 novel by H. G. Wells. Its success set the standard for all such stereotypical stories to come.

In the novel, Martians are said to be tentacled beings, not unlike the Earth octopus. Their interest in Earth stems from the “fact” that the climate of Mars is cooling. They thus travel to Earth in cylindrical spacecraft, apparently launched from Mars with huge space guns (a common representation of 19th-century science fiction, also seen in Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon). The Martians then invade Earth with giant tripodal vehicles armed with “heat rays” and a kind of poison gas known as “black smoke.” Their invasion is brutal, targeting civilians and infrastructure, apparently intent on inflicting maximum casualties. They use a Martian plant, the “Red Weed,” to decimate local plant life. They even use a device to feed on human blood.

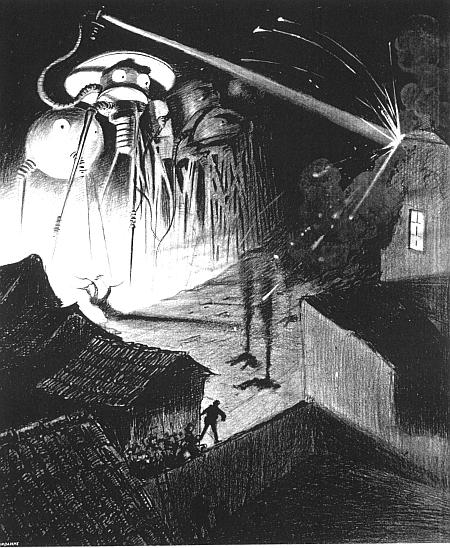

Martian tripodal vehicles destroy an English town, as depicted by the Brazilian artist Henrique Alvim Corréa for a 1906 Belgian edition of the novel.

Of course, the evil Martian invaders are ultimately defeated, due to Earth bacteria to which the Martians have no immunity.

The narrator writes in a journalistic style, which greatly adds to the novel’s realism. This realism, unfortunately, also added to the public’s perception of Martians as hostile invaders.

It’s easy for humans to praise the novel as ahead of its time. Its depiction of “total war” was more or less common to invasion literature, but the particulars Wells used weren’t. Scholars have reveled in how the inaders’ black smoke seems to foreshadow the Mustard Gas used in World War I, the Red Weed evokes a later understanding of what can happen to local ecology due to the introduction of non-native species, and how the heat rays seem to predict lasers. Wells certainly deserves credit for having the Martians defeated not due to any intrinsic human superiority but instead by bacteria. This contrasts to the clergyman, a key character in the novel, who sees the invasion as the Biblical Armageddon and is ultimately killed when his religious ranting draws the attention of the superior Martians.

These more evolved characteristics, however, should not excuse the novel’s extreme racism, which inaugurated decades of depictions of Mars as a dying planet and Martians as a brutal people eager to invade Earth. These Martians might be depicted as technologically superior, but they’re also depicted as surprisingly stupid — such as not being aware of Earth’s bacteria.

A Martian vehicle battling with the warship Thunder Child, also by the Brazilian artist Henrique Alvim Corrêa.

Like later Martian depictions, the anti-Martian stereotypes in War of the Worlds can be placed within a wider context of xenophobia and stereotyping of Earth races. The novel participated in what’s been termed “invasion literature,” which had its heyday from 1871 to 1914 and depicted various invasions of Great Britain. The first major work of this genre was the tremendously successful The Battle of Dorking (1871), which depicted the Germans as a ruthless invading force that used a devastating surprise attack, not unlike the Martians of Wells. Such depictions were common to the genre, although the villains varied, as different nations came to be perceived as the greater threat. Thus, Germany gave way, towards the end of the 1800s, to France. Earth historians now recognize the entire genre as propaganda that speaks more about Britain’s anxiety during a time of international tensions in Europe prior to World War I.

But this recognition has done nothing for Martians, who remain stereotyped as ruthless invaders, in great part thanks to Wells. War of the Worlds was a great success and has remained in print ever since its publication. Imitators began to spring up almost immediately, launching decades of hateful, xenophobic depictions of the Martian people.

These imitators are too numerous to count, especially in a superficial introduction such as this one, intended for a human audience. Of course, many deviate from the Wells formula. Similarly, native peoples of Earth were often depicted as brutal savages, they were also depicted as noble, as a way of criticizing the dominant Earth cultures. This doesn’t invalidate the racism involved, and outlandishly “positive” depictions, such as ones in which Martians are meek, have a racism all their own. These have also been in the distinct minority, while Earth stereotypes of Martians as hostile invaders have continued to this day.

Orson Welles and Anti-Martian Hysteria

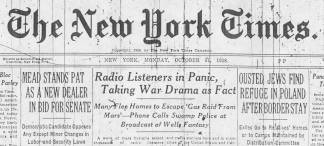

These stereotypes have been extremely successful in media other than novels, such as film and television. And just as Martian stereotypes in novels trace back to Wells and War of the Worlds, Martian stereotypes in other media trace back to the radio adaptation of that novel, made by Orson Welles in 1938.

Seizing on the journalistic style of the original novel, Welles presented his adaptation in the style of radio news reports. Despite broadcast warnings that what listeners were hearing was fiction, many American humans believed the broadcasts to be real. Some, lacking telephones, got together with their neighbors, working themselves into a panic as rumors began to circulate. Several secured or bought firearms. A crowd descended on the landing site, which Welles had moved to New Jersey, causing police to be called. Telephone calls flooded in to the police, newspapers, and to CBS, which aired the broadcast.

In Concrete, Washington, a town of 1000 humans, a cement company happened to have a short-circuit at one of its sub-stations, causing a bright flash of light and a loud sound before the town’s electricity went out, plunging the area into darkness. At the time, listeners were hearing about how the invading Martians had turned toward more rural areas, destroying electrical service and using poison gas. Listeners took the light and sound for an explosion caused by the invading Martians, and the disruption of electricity seemed to prove the point, while also preventing telephone calls to unaffected areas. The next step, many assumed, would come in the form of Martian poison gas.

Some residents took their families and their guns into the mountains. Others prepared to defend their homes. One reportedly took his wife by car to his priest, some 50 miles away, to be absolved before their impending deaths. On the way, he stopped at a gas station where, after failing to pay, he told the attendant that it didn’t matter, since everyone was going to die.

News outlets reported the panic, producing 12,500 stories on it in the following month. It became a major international news story as well, and Adolf Hitler cited it to criticize America. The panic is still studied by humans as an example of mass hysteria or, in contrast, an example of newspapers blowing a story out of proportion.

News outlets reported the panic, producing 12,500 stories on it in the following month. It became a major international news story as well, and Adolf Hitler cited it to criticize America. The panic is still studied by humans as an example of mass hysteria or, in contrast, an example of newspapers blowing a story out of proportion.

But for Martians, these events were particularly alarming. They demonstrated that stereotypes of Martians were more than a particularly insensitive form of entertainment. They showed that large numbers of humans believed these stereotypes and were willing to act upon them. They demonstrated that anti-Martian depictions could easily break into anti-Martian hysteria. In direct response to this incident, Planetary Council Order #7825401 finally passed on Mars, ordering our entire civilization to cloak itself from human view.

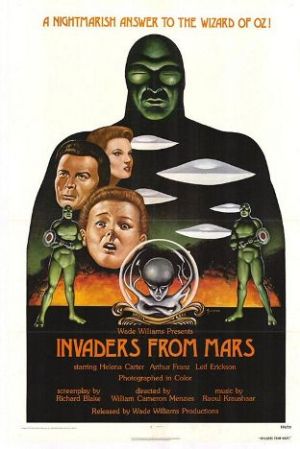

Despite this, Martian invaders would soon become such a staple of Earth fiction and would feature in a string of movies, including the 1953 adaptation of War of the Worlds and the same year’s Invaders from Mars. In a testament to the enduring nature of Martian stereotypes, that same film was remade over thirty later, in 1986.

Marvin the Martian: The Martian Stereotype as Comic Relief

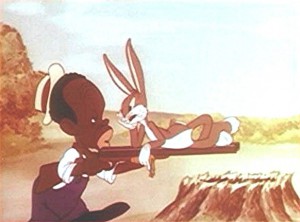

In animation, Marvin the Martian debuted in 1948 as a villain for Bugs Bunny. Given a uniform that parodies that of a Roman soldier from Earth, with a silly skirt and a broom atop his helmet, Marvin was denied even a mouth or nose. Instead, he was given only a round ball of a head with eyes and used for comic relief.

Like the original War of the Worlds, the stereotypical treatment of Martians here should be understood within a larger racist context. Marvin’s treatment was not unlike other racist portrayals involving Bugs Bunny, including the 1941 short “All This and Rabbit Stew” and the 1944 short “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips,” which used racial stereotypes of African-Americans and the Japanese, respectively. By 1948, it was Martians’ turn. The only difference is that, while those earlier portrayals are now considered extremely racist and heavily stereotypical, Marvin the Martian continues to be used today, including in merchandising.

Like past Martian stereotypes, Marvin was obsessed with destroying Earth. His motivation was ridiculous: “It obstructs my view of Venus,” he says. He often spoke in technobabble, referring to what appears to be a simple stick of dynamite as an “explosive space modulator.”

Like past Martian stereotypes, Marvin was obsessed with destroying Earth. His motivation was ridiculous: “It obstructs my view of Venus,” he says. He often spoke in technobabble, referring to what appears to be a simple stick of dynamite as an “explosive space modulator.”

As offensive and hurtful as Marvin was, actual Martians considered him far more offensive because of his incompetence. Bugs Bunny continuously foils him, and he claims that he has been trying to destroy the Earth for more than two millennia. For Martians, this only added to the insult, since Mars could have wiped out Earth any time it liked, yet chose instead to try to help humans (through Planetary Council Order #429371).

Surely, when a stereotype is common enough to be parodied and perpetuated in Bugs Bunny cartoons, it has become commonplace.

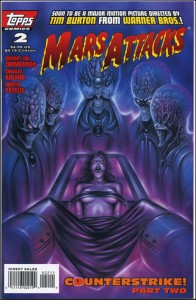

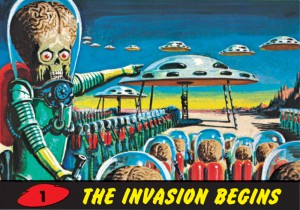

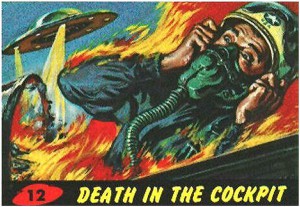

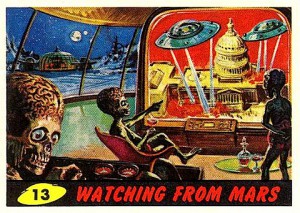

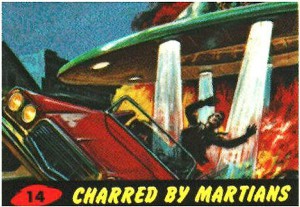

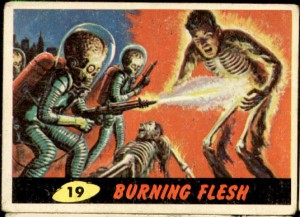

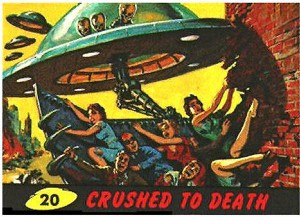

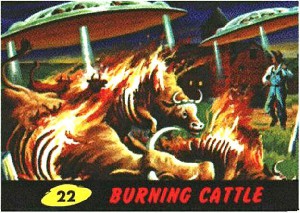

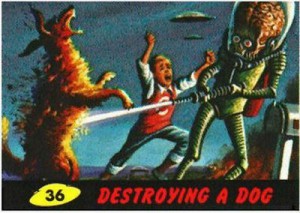

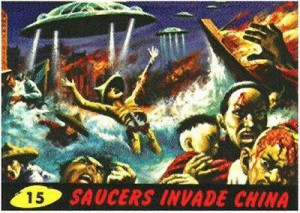

Mars Attacks

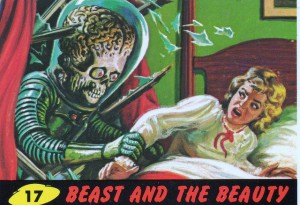

In 1962, Martian invader stereotypes were so widespread that they were even the subject of a series of trading cards given the offensive title Mars Attacks. These Martians were particularly cruel, and many cards featured bizarre forms of torture and mass murder at martian hands. Some of these images were so sensational in their use of gore and sexuality that they spurred parental complaints, which contributed to the line’s demise.

This surely must be one of the most hateful depictions of a people in the history of the world. Again and again, Martians are depicted as gleeful and creative sadists, eager to slaughter humans and cause widespread carnage. The evil of these stereotypical Martians even extends to animals, which they seem to kill with almost as much glee as they do the humans.

Tellingly, the story told by the cards concludes with a fleet of Earth ships retaliating by committing genocide and destroying the entire planet of Mars.

If you consider these cards fun, please consider how you would feel if, instead of Martians, they featured maligned human groups. I doubt Negros Attack would have gone over quite as well. Nor Homos Attack, featuring creative and sadistic mass murders perpetrated by homosexuals.

But perhaps that’s why Mars Attacks existed in the first place. After all, like other stereotypical portrayal of Martians, Mars Attacks demonstrates that anti-Martian stereotypes go hand in hand with human racism. Cards that showed the callous devastation inflicted by the Martian invasion around the world provided ample opportunity to stereotype other groups of humans, even as the main focus was on maligning Martians.

Just as racial human stereotypes have often entailed a sexual component, such as stereotypes of African-Americans as seducers and rapists of white women, so thoughtless is the hatred of Martians that Mars Attacks depicts Martians as doing the same, despite that human women would doubtlessly be incompatible with Martian physiology. Of course, the women being menaced are attractive blonde-haired white women, to underline the parallel to miscegenation. The images are even composed in the same threatening manner.

This was hardly the only instance in which Martians were depicted as hungry for human women, in a style instantly recognizable to those who study human racism. In the heyday of Martian invader movies, this particular stereotypical aspect was made the basis for an entire film: 1968′s Mars Needs Women.

This was hardly the only instance in which Martians were depicted as hungry for human women, in a style instantly recognizable to those who study human racism. In the heyday of Martian invader movies, this particular stereotypical aspect was made the basis for an entire film: 1968′s Mars Needs Women.

In yet another testament to the enduring nature of these stereotypes, the card series returned in the 1980s, with new cards augmenting the originals, and with the addition of comic books recounting and expanding this obviously anti-Martian story. In 1996, the story was even adapted as a big-budget Hollywood film, directed by Tim Burton and starring Jack Nicholson.

In yet another testament to the enduring nature of these stereotypes, the card series returned in the 1980s, with new cards augmenting the originals, and with the addition of comic books recounting and expanding this obviously anti-Martian story. In 1996, the story was even adapted as a big-budget Hollywood film, directed by Tim Burton and starring Jack Nicholson.

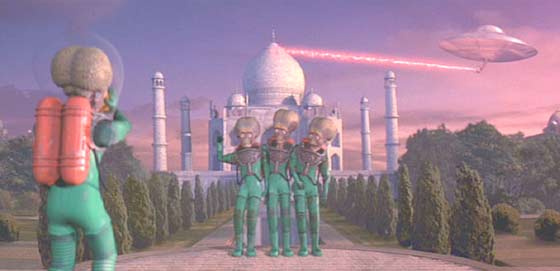

In the film, the Martians delight in creative carnage, parallel to the original card series. Although Mars isn’t destroyed at the end, these Martian stereotypes claim to come in peace, even as they slaughter humans in the streets with ray guns.

In the film, the Martians delight in creative carnage, parallel to the original card series. Although Mars isn’t destroyed at the end, these Martian stereotypes claim to come in peace, even as they slaughter humans in the streets with ray guns.

The moral apparently being that you can’t trust a Martian: even when he’s offering peace, he’s only going to kill you and your family — and probably burn your dog alive and rape your daughter too.

Conclusion

These stereotypes might not be as widespread as they once were, but there can be no doubt that they continue. The hateful depictions of Martians, begun with War of the Worlds, has now entered its second century. One need only look at Stephen Spielberg’s 2005 cinematic adaptation of that novel, a remake of the 1953 film, to see that the stereotype of Martians as sadistic people itching to brutally invade the Earth remains very much alive and well.

What is most alarming about this fact, to many Martians, is that these stereotypes have continued despite our civilization being cloaked from human detection. In 1965, NASA’s Mariner 4 completed a fly-by of Mars, followed by several other probes, beginning in 1971. Martian policy worked, and humans now had evidence that Mars was lifeless. Yet this did little to break the pattern of Martian stereotyping.

Depictions of Martians may be seen by humans as increasingly far-fetched, but they remain as hateful and stereotypical as ever. In fact, the case could be made that such depictions have acquired an element of nostalgia, insulating them from criticism. This is true despite increasing awareness of stereotypes generally. Certainly, few humans would defend a big-budget Hollywood movie using blackface as charmingly nostalgic. No, that’s reserved for Martians.

113 years after War of the Worlds, Martians increasingly seem to be the last Other, whose stereotypes are treated as entertainment, instead of the dangerous hatred that they are.

As not only the world grows smaller, so to does the Universe. As your article suggests, it is high time we turned back the Stereotypes in lieu of thoughtful analysis and commentary on Martians.

While the term “alien” does bring up a host of problems socially and economically now, it is not a term we need let die. Instead, perhaps we can re-brand the word as a term for tolerance and understanding, but as the implied meaning stands there is still a differance (to use Derrida’s term) there. There is an infinite gap between subject and alien/other. While that gap may never be crossed, it is great to see articles like your Dr. Darius that promote the attempts, however so unending, to bridge that gap.