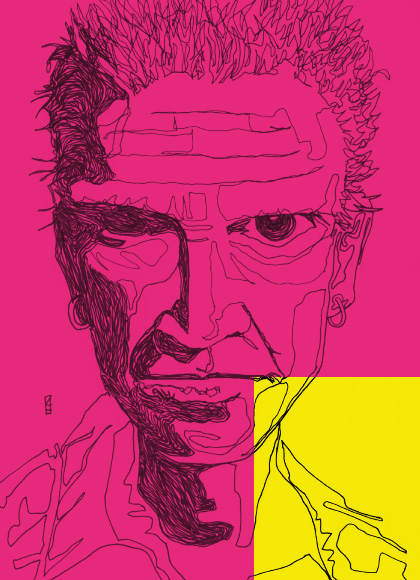

Billy Idol’s music makes my dick hard. So does baseball: playing it, watching it in person, on TV, listening to games on the radio, trading and collecting bubble gum cards, you name it. Combine both passions and you have the best part of my childhood: a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup of a good time that made the prospect of adulthood bearable.

Billy first rocked my world when I saw his music video for “White Wedding.” Then came “Dancing with Myself,” and “Rebel Yell.” The latter sealed the deal of my fanaticism. Not only did it have a mean Steve Stevens guitar riff, but also Billy’s sneer was never more badass, never more charming than it was in that video. That I was 13 when I first saw it appealed to my “fuck the world” mentality. Further, whenever I played Billy’s records or watched one of his videos on MTV, my father would groan, then go on a tirade on how my time would be better spent listening to Phil Rizzuto broadcast Yankee games on WPIX, as opposed to watching “Limey Pussies” on MTV. With a Rebel Yell, I cried more, more, more.

Fortunately for me, my best friend Matt Fleming shared my enthusiasm for Billy and baseball, and we played as much music on our boom boxes as we did pickup games. Matt, who was better known as “Matty-Ass,” was also the best ballplayer on Teed Street: our block. He was also the organizer of our neighborhood competitions, which meant that he was in charge of selecting the background music for our games, “Our soundtracks,” as he called them.

More often than not, we played stickball rather than baseball, because the Memorial Junior High School playing field, the closest one to our block, was usually gated shut, and security guards hung around them like spiders.

Further, security had been increased because of the sump that was located about 100 yards beyond the outfield fence of the baseball field. The sump area had become a gathering place for the teenage kids of our neighborhood to deal and smoke weed, drop acid, give and receive head. The sump itself had also become a watery cemetery of sorts for prosthetic legs, cat corpses, bicycles, burned pots, and cameras, among other mediocre tragedies and throwaway products, and people who lived nearby were tired of “all the ruckus.” Matty-Ass called it “Booty Hill,” which came to be how everyone referred to the baseball field.

Braids of smoke continued to drift over the sump like wraiths on weeknights, the increased security notwithstanding. Even better, Booty Hill was open to the public on the third Saturday of every month, which we took advantage of, so long as it wasn’t raining.

Today was not one of those days. Earlier in the week, Matty-Ass and I had a heated debate during study hall about who the better catcher was: the late Yankee team captain Thurman Munson or Gary Carter, the Montreal Expos slugger whose youthful exuberance earned him the nickname “Kid.” A perennial All-Star selection, Kid had become Matty-Ass’s favorite player after watching his performance in the 1981 midsummer classic at Municipal Stadium, the old digs of the Cleveland Indians, where he slugged his way to the game’s Most Valuable Player award with two home runs. I said Thurman. Things escalated from there.

We spent the rest of the class period and walk home from school debating the point. By the time we reached Teed Street, we determined that we would settle the argument over a game of baseball. Matty-Ass and I would assemble teams compiled of any 12 people of our choosing, no more or less. Both teams would play each other at Booty Hill. The catch was that our primary role in the game was to manage our respective teams. Neither of us could play in the game, other than to pinch-hit. If either of us decided to do so, we could only have one at-bat, and not play in the field. The losing manager had to buy pizza for the entire winning team and wear either a Yankee or Expo cap for a week, in Thurman’s or Kid’s honor. Game on.

So there we were at Booty Hill on the third Saturday of May in 1984: The Matty-Ass All-Stars versus Joey’s Juggernauts. There were two outs in the eighth inning, and my next-door neighbor JJ Alzado was on third. The Matty-Ass All Stars were winning 4-2. My friend Timmy Cream Cheese left the game to go to his cousin’s Bar Mitzvah, so I was batting in his place.

I stepped in the batter’s box, and tapped home plate—the dish with the tip of a Graig Nettles Louisville Slugger bat I got for Christmas. I hoped that some of Graig’s home-run power would rub off on me. Billy crackled from the boom box:

It’s a nice day to start again. Come on

It’s a nice day for a white wedding.

It’s a nice day to start again.

Eddie Sacks gripped the ball. His first finger was on top of it and his middle finger was pressed down firmly on the seam. Then he placed his thumb underneath, and curled the other two fingers toward the left side of the ball. The deuce: a curveball was coming my way.

Swing and a miss. Eddie smiled.

“All day! The deuce beats the Dago. All day!”

I stayed in the box. “Don’t think,” I said to myself. “Don’t think.”

Eddie re-gripped the ball. This time his first and second fingers were on top of it, away from the seams. A fastball was in my immediate future.

I hit the ball well, but it sliced foul in the metallic bleachers behind the first base line.

“Ha!” Eddie yelled. “Whatsamatta, Dago Boy? Did yo momma have sour milk when she breast fed you?”

“You know,” I said, “your birth certificate is an apology letter from the condom factory.”

Eddie promptly threw the ball at my head. I hit the dirt.

I got to my feet and stepped back into the batters box, relieved that my ears were still attached to my head. Eddie gripped the ball just as he did for the previous pitch. I choked up on the bat as Billy sang on:

There is nothin’ fair in this world

There is nothin’ safe in this world

And there’s nothin’ sure in this world

And there’s nothin’ pure in this world

Look for something left in this world

Start again

I took a healthy cut: this time I hit Eddie’s heater dead-on. The ball was headed towards the sump. Thank you, Graig Nettles, and thank you, Badass Billy.

Rob “Robby Rabbit” Dominguez, who had the fastest wheels in town, chased the ball down. He jumped up and pulled it out of the air, just before it cleared the fence. There were now two outs, but JJ crossed the dish.

“All day,” the Armpit yelled.

Eddie kicked mud off the mound. He then struck out my good friend and corpulent catcher Kevin O’Hagan on three pitches.

“Take a seat, Captain Yogurt.”

Kevin smirked.

“Can I borrow yo momma’s face a few days while my ass is on vacation?”

Eddie started to charge Kevin, but Matty-Ass, Steve Manchester, and Salt Peter Woods got in his way and led him to the All-Stars’ dugout.

Matty-Ass led off the next inning. The Armpit got him out on a pop-up behind home plate, where Kevin caught it. One out.

Steve Manchester then hit a single on the first pitch. Eddie dug into the batter’s box, veins popping out of his neck.

The Armpit stepped off the mound. Instead of sniffing his armpits like he usually did before he threw a pitch, he gripped the ball, and started mumbling. He then looked directly at Eddie.

“Fascinating. It says here that you won’t hit this next pitch.”

“I bet it also says yo momma so fat, Mount Everest tried to climb her.”

The Armpit bent his head towards his right arm. Sniff, sniff.

Steve took a big lead from first base as the Armpit went into his wind up. Eddie swung at the first pitch and crushed the ball.

Salt Peter dove to his left and missed the ball. Steve rounded third and crossed the dish, uncontested.

Other than another than a triple by Robby Rabbit, no one else got a hit or reached base for the rest of the game. Not that it mattered: the Matty-Ass All Stars emerged victorious with a score of 5-3.

Matty-Ass slapped my back. “Good game, Bro. It could’ve gone either way.”

“Thanks, Man.”

“Honest, it could’ve gone either way—like your Mom.”

I clenched my left hand into a fist. Then we both burst out laughing and made our way to Booty Hill’s back gate. I glanced at the sump, and Matty-Ass slapped his sweat-stained Expo hat on my head, the taste of fresh mozzarella melting on our tongues, ears dripping with Billy’s inimitable 1980’s hard-rock wisdom:

Neighbor to neighbor

Door to door

Enjoy the crime

You do your time

Never been nothing before

* * *

Billy’s last big hits were “Cradle of Love” and “Shock to the System.” “Cradle” earned him a Grammy nomination in 1991. He rewrote the lyrics for “Shock” after witnessing the Los Angeles riots of 1992. Since that time, he’s also had a few small roles in movies, including The Wedding Singer and The Doors. He continues to make music and tour worldwide.

Kid died in February of 2012. He had been diagnosed with Stage 4 glioblastoma, a particularly aggressive form of brain cancer, in 2011. Kid’s doctors informed him that his cancer was inoperable, but he underwent radiation chemotherapy to shrink his tumor. By most accounts, Kid maintained his characteristic high spirits and public profile, even attending of the opening day for Palm Beach Atlantic University’s baseball team, who he had been coaching since the 2009 season, after spending the previous season at the managerial helm of the Long Island Ducks in the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003.

Tonight I am watching a VHS recording of the 1984 All-Star Game, marveling Kid as he laughs in the home team dugout of Candlestick Park, as if he’s just heard the greatest joke ever told. Although I can’t hear the laughter, I imagine the joke, and smile with him, delighted in the possibility that at least one among the players gathered in San Francisco that July night seemed appreciative for the opportunity to be there. The tape is a bit grainy and slow, but it doesn’t keep Kid from strapping on his leg pads with gusto; his curly locks of auburn hair overflowing from his blue, white, and red batting helmet.

I fast-forward the tape to the bottom of the second inning. With the score tied at 1, Kid hits a solo shot off of Dave Stieb, the mustachioed ace of the Toronto Blue Jays staff, to give the National League the lead. Dave shakes his head and smirks as Kid rounds second base, en route to his second career All-Star game MVP award. Watching this moment again returns me to how I felt when I first saw it: it’s as if I am one of Kid’s teammates; that my semi-decent wheels and batting eye just might have taken me to San Francisco that night, if I had worked at it. Perhaps it has something to do with the camera angle, which gives the viewer the perspective of his colleagues, rising from the bench in the dugout. Regardless, I can’t help but join Goose Gossage, Ozzie Smith, Mike Schmidt, and the rest of his teammates as they give Kid a round of applause.

Watching Kid cross the dish reminds me of a phone conversation I had with my father early last year. Our conversation was brief, and went something this:

“Mojo! What’s doin’, Kid?”

“Hey, Pop. Not much.”

“You comin’ home for your brother’s birthday? It’s in two weeks.”

“We’ll see. How are you?”

“I’m lousy, Kid—because of the Kid.”

“Say what now?”

“Damned Limey Pussy music! It’s making you deaf!”

“Huh?”

“The Kid’s dead.”

“Which kid?”

“Gary Carter.”

“I know. It’s awful.”

“I should’ve gotten his autograph when I had the chance. Death sucks.”

“How’s everything else, Pop?”

My father has Diabetes, and had been experiencing some unforeseen side effects from his medication. He didn’t give any specifics about the effects or the medication in question, other than it made him feel “sad;” his stomach “explosive.”

“I’m here,” he said. “But I gotta go. The Ducks game starts in a few. It’s fireworks night. I have to fight explosion with explosion. Maybe some Pepto-Bismol.”

“Good idea, Pop.”

“Talk soon. Game time, Mojo.”

As soon as the call ended, it occurred to me that it was February, so there was no game being played. My father had called to share his grief, which is to say that he wanted me to listen, more than converse with him. As much as I enjoy talking with people, my conversations with my father have impressed the importance of listening to what someone else is saying. This brings me to the latest lesson I’ve learned in my ongoing investigation of what accounts for my fondness for baseball: I fancy the crack of a bat as much as a fat bass line; it is as sonorous to hear its sounds as it is fun for me to watch or compete in, even when I am unable to do so. If music is “the food of love,” as William Shakespeare wrote, then Billy Idol and baseball are two of the main reasons why I play on.

I wanted to call my father back to tell him about my discovery, but I thought better of it. Instead, I stopped watching my tape of the 1984 All-Star game and envisaged potential highlights of the upcoming season. I thought of Graig Nettles tipping his hat to the crowd during player introductions during the pregame ceremonies of Old-Timer’s Day at Yankee Stadium. I thought of my father on the Fourth of July, watching fireworks explode over Citibank Park at the conclusion of a Ducks game from his mezzanine seat. To ignited firework shells, every voice is booming: rebel yells of sorts, filling the soperssata-thick Long Island summer air with its green, silver, gold, red, white, and blue phrases, putting mine and my father’s hopes into luminous words as they move down the smoke-lined page of the sky in different directions.