I.

Because it was the thirty-third anniversary of the overthrow of their old government, and because it, too, happened to be a red autumnal moon, and because the calf came out hindquarters first, complicating the birthing thereby killing the mother, the migrant ranch hands determined that the birth of the bull was an ill-omen and to continue its lineage would mean a curse on every one of them and their strongest born sons.

The bull lay atop its placenta, chewing it like a toy, as its mother lay splayed, bloodied, and dead. Five ranch hands stood semicircle around it, determining just what evil now lay before them and wondering how might they may rid themselves of it.

“We could burn it,” one younger hand suggested. “In the truck I have some gasoline. We burn it and the mother. That would put things right.”

The oldest hand, a shift boss, thought about the suggestion for a while. He did not speak as he crouched near the calf, looking at it, and patting its soaked hide. The calf stretched its head toward the man, smelled him, and licked his sleeve, then cleaned its nostrils of the residual amniotic fluid with its large tongue.

The old shift boss spoke. “We do that here and we burn the barn. We do it out in the field and Ranch Boss will know we burned his new bull.”

The other four agreed. The young hand who made the suggestion did not protest.

Another hand offered a solution. “We slaughter it. Say it was a difficult birth—that’d be no lie. The cow’s already dead, so Ranch Boss will believe the calf would be dead too. We eat them both and then it would set things right.”

The old migrant cowboy rose, stepped lightly away from the calf, and brought the one who suggested the slaughter outside the barn, away from the group. As they walked away, the calf stretched its forelegs, reaching out for them like a spider grasping at prey.

They talked, hushed out in the open prairie, as all the land was open prairie. Under the red moon the old man said, “We eat this thing and who knows how that evil will fester within us. Do you have the strength to fight it?”

“Oh no, Pedron, we don’t eat it. We feed it to Ranch Boss and his family.”

“And then what? They get the evil of our past. We brought this. Not them. It was on our revolution’s eve. It was under our Red Moon. It happened before our eyes. If our evil mixes with theirs, what then?”

The young hand who made the suggestion still seemed dissatisfied, but he knew there was no way of swaying this old revolutionary when set in his ways, for he was the only of the group to have fought in those battles that left a wound so deep it hadn’t healed. He was the one who was missing fingers and had the dark starburst scars on his back. It was his family who had their throats slit. And it was he, with that same ivory-handled knife he carried to this day, who slit the throats of those he never spoke of. And it was with that same knife that he cut the cow’s womb, from utter to anus to save that cursed bull.

Once a decision was reached, they returned. There in that uncertain light, the remaining three men had moved closer to the calf. It was now standing and mewing in the thick, congealing pool of its mother’s blood. It shook all the fluids off itself, drenching the men, and they all danced in the spray, boots pounding in the blood, as if it were an August storm roiling over the plains, ending the drought of a long and wicked summer.

II.

He sent his mama under the floorboards the moment he returned from the high bank to report the white boat was coming up the river.

He sent his mama under the floorboards the moment he returned from the high bank to report the white boat was coming up the river.

“Take Angeline and Timmy and get with the preserves. They comin’!” was what he said.

Timmy and Angeline were crying and Mama protested, but with Pa being stayed-gone and Jacob being drowned two years since, he was the only one willing to take up the rifle.

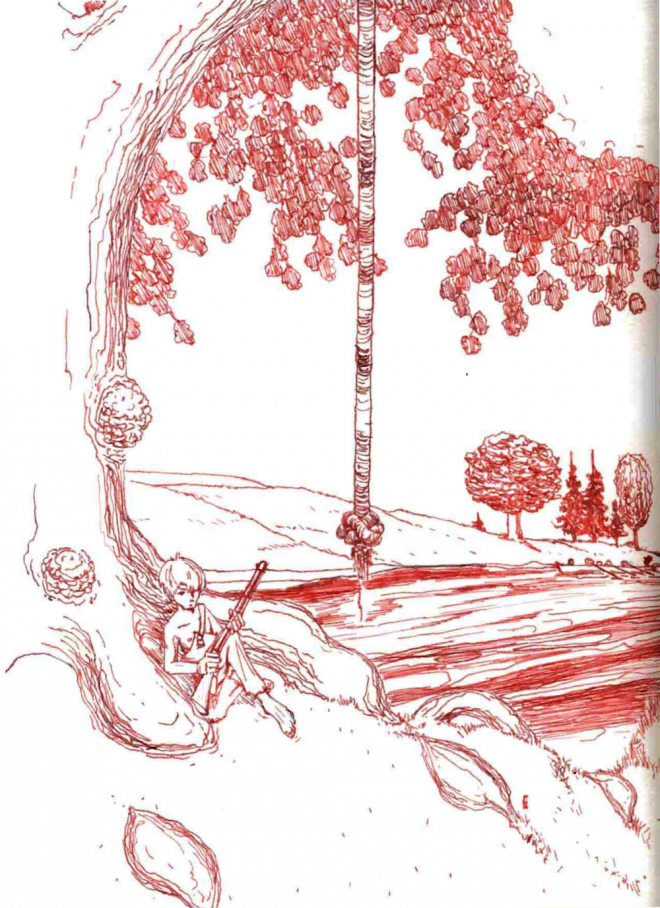

Down by the bank, just a few paces below the high banks where he’d seen them coming from far off, he hid under the oak that leaned out into the river. Hanging from that tree was a twenty-foot length of plaited rope for swinging back when the boy would swing from it like a child with his brother and sister, back before Pa ditched. With the rifle clutched in his hand—staid and steady—he mused on the lifelessness of that dangling thing for a moment, forgetting the grown men workings he found himself currently in.

The boat came around the bend the way he suspected it would, getting swept by the strong current and bringing it wide. The eight or so men, guarded up to their chest by the gunwales, let a few “heave ho’s” and “whoanellies” as the boat careened toward the bank. Long, gray oars extended further out the sandbar side, and a few quick strokes were struck, but the current continued its quiet fury, pushing it ever more into the bank until it crashed with a dull thud and got hung up in the rootwork and brambles that reached out from the bank and clung to the boat. A few of them swore at each other, but the leader-looking man, the one with the tall hat who stood at the back, barked some orders. Two of them scurried to cut the roots loose—one with a flat iron machete, the other with an oar.

They weren’t at the moment in range, and they’d be a touch out of range for a solo deer, but a shot was chambered anyway and the few extra shells in his breast pocket were accounted for. With a quick calculation the boy figured if he got three or four of them right off—one shot a piece—he could take his time with the others. Maybe double up the shots on a few of them who lay in misery. He bellied himself forward a little to get his head above a large gnarl of root that kept him well-hid but also obstructed his view. He used a knuckle of the root to steady his muzzle. Once steadied, he aimed it right at the three red numbers on the side to test his iron sights. For a moment he mistrusted the aim as he could not recall the last time his Pa’s gun had been properly sighted. But then an overwhelming sense came over him that dead Jacob was there, guiding that boat to him, putting them in range so he could show them where to. With one last check to his chamber and action, he grew to trust those sights—his Pa’s gun—more than anything in his entire life. Of all the things he done in his life, this moment here was like a gate to a whole string of moments that lay before him.

The leader-man continued to shout as the boat came loose and the oars were slid out, this time on both sides of the craft like some giant insect setting its leg upon the water to come charging. As it neared and it became evident that the angle they were at kept them protected, the boy’s gaze fell again to that dangling rope over the water.

He had swung out into those green, dark depths before, silhouettes of carp visible as he tumbled mid-air—Jacob there on the shore, just a blur of flesh as the world rotated itself out of understanding and into a place of holy mess (though only for a moment) as the tumult was sure to end the way it always did: in a sucking heave of wet darkness and silence. The flailings, which seconds ago meant nothing—the swipings of a fish in phantom waters—now became something real, a possibility, a power to move, to bring oneself from that which was chaos and darkness to that which is a brother, no longer a blurred spirit, but a fully formed man, tugging a dripping and shivering kid from the water and saying things that sound cruel, but from him are not at all.

A man in uniform stepped to the bow and made swift preparations behind a large gun on a swivel. The rowing stopped, the oars suspended above the water. The boy raised the rifle to his eye as a command was shouted from the rear of the vessel. Quicker than a blink, he saw the rifled spin of the coming shot.

The earth fell away. The boy tumbled, just as he had not so long ago. The dark waters came full at him. His rifle hit the waters first and he knew sure as spit that Pa would be peeved. Then there were many confusions and questions fighting their way out of his quickening yet fading mind, all of them addressed to Jacob, but not one wondered why.

III.

There were three men on the hunt. One was prone and old, staring up at the dark dark sky contemplating the movements of the earth and universe in the way old trappers do: with lingering thoughts on pelts and blood and how them critters go on fixing themselves in the afterlife. Another man, a tired man, leaned back on his haunches chewing the longleaf and spitting every so often, making a sort of game out of it, trying to cover a hot stone with his green juices before they sizzled away to tobacky heaven. The last man lay with his back to the fire, warming the place he once dreamt of having wings.

The Old Trapper and Tired Man spoke softly, paying mind not to rouse death once took hold, but also paying no mind to the echoey ker-chug of the whiskey jug they passed back and forth.

The Old Trapper spoke first. “I figure I have you go out to the ridge and look over the slough. Saw four-five of them out there this mornin’.”

“That a fact? You seen them this mornin’?”

“Sure did, but it was gray light so can’t be too sure, but I know a nichee the moment it moves. You know that ’bout me.”

“I knows plenty about you … I also knows you ain’t seen shit.”

They resumed their contemplations, one thinking on the many creatures that have been done up and killed and the other on the creatures that a man says exist as sure as stones and fire, but ain’t no realer than the dreams of their companion heating his back on an already warm evening. And this double-hotness that their compadre tolerated bothered the both of them though neither spoke on it.

“You see that man there,” the Tired Man said.

“I sees him.”

“Now if I were to ask him if he saw them coots this morning, I’d go out to that ridge without complaint. You see he’s a trustworthy fellow and you … well, you’re just a fellow,”—spit, a sizzle, a flash of anxious fire eating the man’s juice.

“I don’t see your point, friend. Give me that jug,”—the swig, the kerchug, and the hot-laugh burn—an effigy of an old trapper’s unkindnesses.

The Tired Man peered over that fire toward the Old Trapper, who had that trapper smile on his face, which contained all the lands he been to, as if they were all the lands worth going to and none else were worth the drop of a boot heel in their direction.

“I says I call you a liar. That’s all. You’re a liar. You ain’t seen them.”

Looking back, the Old Trapper saw what he would call the tracks of a snow rabbit. He saw them bright as a winter noon sun on a windswept lake. Them tracks were there, hustling through that fire’s white light and it was this young black-haired man with the 1873 who made them tracks. He’d seen it. He’d seen it before. If only fellas like these could look into the nights he had seen. All the living things that’ll kill you while alone in the dark. Those are the things these boys ain’t seeing no more.

“You look over your shoulder much?” the Old Trapper said, his yellow twisted teeth emerging from his lipless smile.

“What’s that s’posed to mean?”

“Just nothin’. Nothing is all. Means as much as them invisible nichees I’d a had you chasing in the morning.”

“Ain’t never look over my shoulder.”

“Good good. No man should do such a thing.”

“Only men I see do that come to see the Reaper was always in front of him just waiting for him to look behind.”

This pleased the Old Trapper who’d lived a life of the burning rye and frozen legs, so he let out the old trapper yell, sending the night astir and coaxing in a far-off coyote as accompaniment. So man and beast filled the night like a moonrise at midday, and this raucous did suck the blood through the jawbone of the Tired Man’s face.